↘

DO—

NOTHING—

MACHINES

In Praise of Idleness.

Industrialised societies strive for productivity and efficiency. In these systems, doing nothing often has a bland aftertaste or is itself subject to a strict schedule. We mark time for relaxation in our calendars, monitor and optimise our sleep. Have we long forgotten the art of idleness, the dolce far niente – the sweet nothing? Between studies, work, family and self-expression, where is the freedom to simply be?

The devaluation of idleness since the Reformation is a relatively recent development. In ancient times, idleness was considered a privilege of free citizens and the nobility, and essential for the development of art and culture. In the Middle Ages, the spiritual mystic Hildegard von Bingen even warned against excessive activity: »But man must beware of killing his body by too much work« (1).

The Alcoa Solar Do-Nothing Machine by Ray and Charles Eames (1957) symbolises the explorations of this course. It was not designed to fulfil a ‘practical’ function (2). It is a fascinating dance of colour and movement with no utilitarian purpose – an ode to curiosity, playfulness and the joy of pure observation of movement. The machine challenges our conventional understanding of function and utility and reminds us that there is value in pure experience. In these unstructured moments of leisure, the mind can wander and creativity can flourish.

From the aimless walk as an activity of intrinsic value, to the power nap and the sobremesa, the Spanish culture of resting after a meal (3), to procrastination, the course looked intensively at doing nothing, at leisure and at breaks and what they mean to us and our social interactions. In contrast to laziness (and doomscrolling), the projects are designed with and for the conscious decision to pause, perceive and reflect.

The devaluation of idleness since the Reformation is a relatively recent development. In ancient times, idleness was considered a privilege of free citizens and the nobility, and essential for the development of art and culture. In the Middle Ages, the spiritual mystic Hildegard von Bingen even warned against excessive activity: »But man must beware of killing his body by too much work« (1).

The Alcoa Solar Do-Nothing Machine by Ray and Charles Eames (1957) symbolises the explorations of this course. It was not designed to fulfil a ‘practical’ function (2). It is a fascinating dance of colour and movement with no utilitarian purpose – an ode to curiosity, playfulness and the joy of pure observation of movement. The machine challenges our conventional understanding of function and utility and reminds us that there is value in pure experience. In these unstructured moments of leisure, the mind can wander and creativity can flourish.

From the aimless walk as an activity of intrinsic value, to the power nap and the sobremesa, the Spanish culture of resting after a meal (3), to procrastination, the course looked intensively at doing nothing, at leisure and at breaks and what they mean to us and our social interactions. In contrast to laziness (and doomscrolling), the projects are designed with and for the conscious decision to pause, perceive and reflect.

(1) von Bingen, H. (2024) Heilige Inspiration in Weisheit der Welt (Band 23).

(2) Neuhart, J., Neuhart, M., Rams, R. (1989) Teams Design. The Work of the Office of Charles and Ray Eams, New York.

(3) Randolph, M. (2018) A uniquely Spanish part of the meal. www.bbc.com ↗ Accessed Februar 13,2025.

Supervision Prof. Judith Glaser

Summer Term 2025

(2) Neuhart, J., Neuhart, M., Rams, R. (1989) Teams Design. The Work of the Office of Charles and Ray Eams, New York.

(3) Randolph, M. (2018) A uniquely Spanish part of the meal. www.bbc.com ↗ Accessed Februar 13,2025.

Supervision Prof. Judith Glaser

Summer Term 2025

↘

SLOMA

ThuyVy Nguyen

›The relaxing coffee break for everyone.‹

Sloma is a coffee machine that turns coffee preparation into a mindful, relaxing experience. The design was created based on the idea that people with very different approaches to coffee could be connected by a shared device, mediating between functional simplicity and sensory experience. Sloma is aimed at people with no prior knowledge who usually consume coffee casually, as well as coffee fanatics with high standards of preparation and taste. Rather than focusing on technical complexity or pure efficiency, Sloma prioritises visibility, tranquillity and accessibility. Its transparent design allows you to see the brewing process directly. Two rotating water wheels direct the coffee into the cup, lending the process a meditative quality.

Sloma is a coffee machine that turns coffee preparation into a mindful, relaxing experience. The design was created based on the idea that people with very different approaches to coffee could be connected by a shared device, mediating between functional simplicity and sensory experience. Sloma is aimed at people with no prior knowledge who usually consume coffee casually, as well as coffee fanatics with high standards of preparation and taste. Rather than focusing on technical complexity or pure efficiency, Sloma prioritises visibility, tranquillity and accessibility. Its transparent design allows you to see the brewing process directly. Two rotating water wheels direct the coffee into the cup, lending the process a meditative quality.

The product is deliberately straightforward to use. The parts are easy to take apart and clean, and are made of single-origin materials. This makes Sloma sustainable and durable. Inspiration for the design came from a lamp and a water toy, whose clear movements were incorporated into the design.

It provides a framework through which users can engage with their coffee routine at their own pace. Preparing coffee becomes the focus of the break. It's an invitation to slow down for everyone.

It provides a framework through which users can engage with their coffee routine at their own pace. Preparing coffee becomes the focus of the break. It's an invitation to slow down for everyone.

↘

![]() Lücke

Lücke

Florina Rall

Lücke's approach is to

›have less, do less‹.

This is a bag that can be used both as a spacious bag for uni or school and also as a place to lie down. With a zip, any ›gap‹ in your day can be transformed into an opportunity to take a break. You can spontaneously ›do nothing‹ or carry less to ›do nothing‹.

This is a bag that can be used both as a spacious bag for uni or school and also as a place to lie down. With a zip, any ›gap‹ in your day can be transformed into an opportunity to take a break. You can spontaneously ›do nothing‹ or carry less to ›do nothing‹.

↘

Licht/Spiel

Amalia Kasdepke

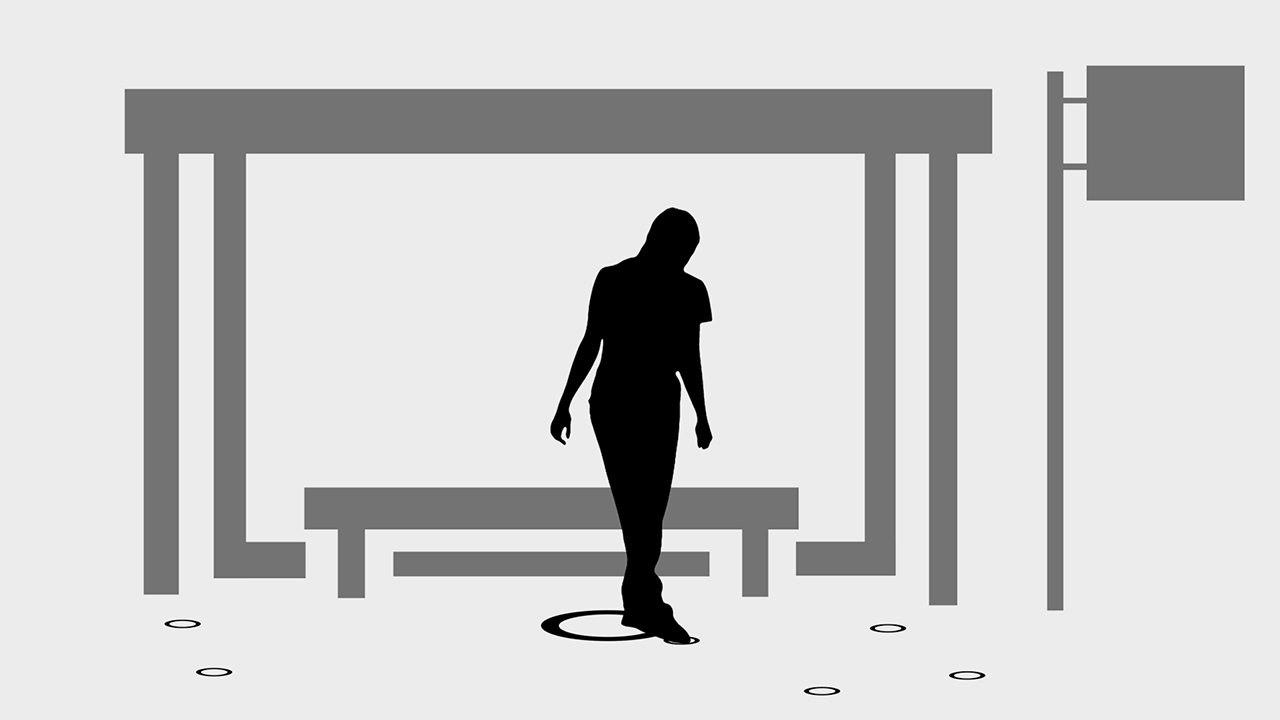

Licht/Spiel is an interactive light installation that brings

playful breaks into the everyday routines of adults. Installed at bus stops –

places where people frequently wait – it invites spontaneous interaction

through projected games inspired by natural childhood phenomena like bubbles,

puddles, or pinecones. The games are intuitive, seasonal, and adaptable to the

number of people present. At night, the installation adds a second layer: soft

light circles track individuals at the stop, enhancing both presence and safety.

Licht/Spiel turns an ordinary waiting space into a moment of

pause, reflection, and connection – without requiring effort, instructions, or

prior intention. It offers a gentle reminder that playfulness doesn’t have to

end with childhood, and that public space can be both functional and poetic.

↘

Krisel

Joy Rammig, Paul Schulz

»Distraction is a strategy in Service of the work.«

Rick Rubin, The Creative Act (2023)

This project attempts to address the issue of mental blocks during creative work. Creativity cannot be forced, which can cause problems for professional creatives. We have observed and experienced that distraction can be an effective way of dealing with mental blocks. However, we live in a world of distractions, so the difficulty lies in finding the right distraction at the right time.

Rick Rubin, The Creative Act (2023)

This project attempts to address the issue of mental blocks during creative work. Creativity cannot be forced, which can cause problems for professional creatives. We have observed and experienced that distraction can be an effective way of dealing with mental blocks. However, we live in a world of distractions, so the difficulty lies in finding the right distraction at the right time.

Krisel is a tool that gently reminds you to reflect on where you are in your creative process without causing stress or time pressure, both of which are catalysts for mental blocks. It is deliberately analogue and counteracts the abundance of digital distractions that surround us. The object itself can be used as a haptic distraction or as a token to symbolically start or end a creative flow state. However, its main intention is to serve as a gentle reminder to take an early break and avoid getting stuck in a mental block.

↘

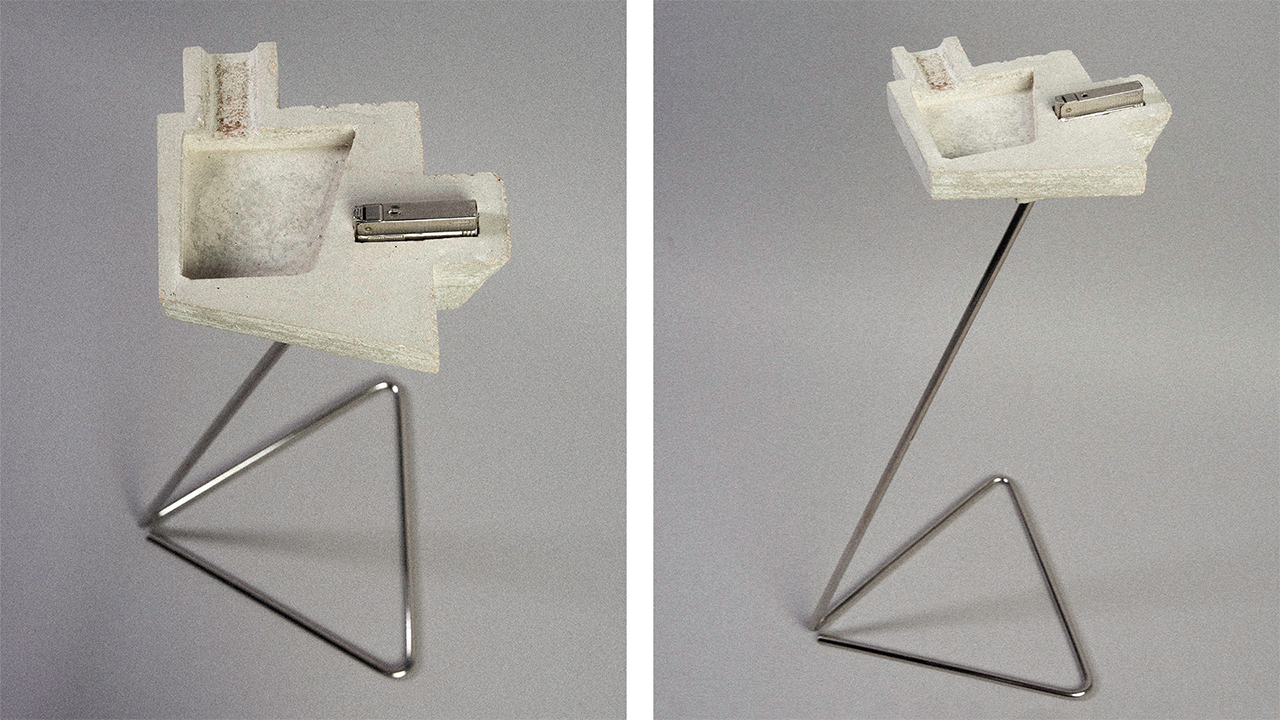

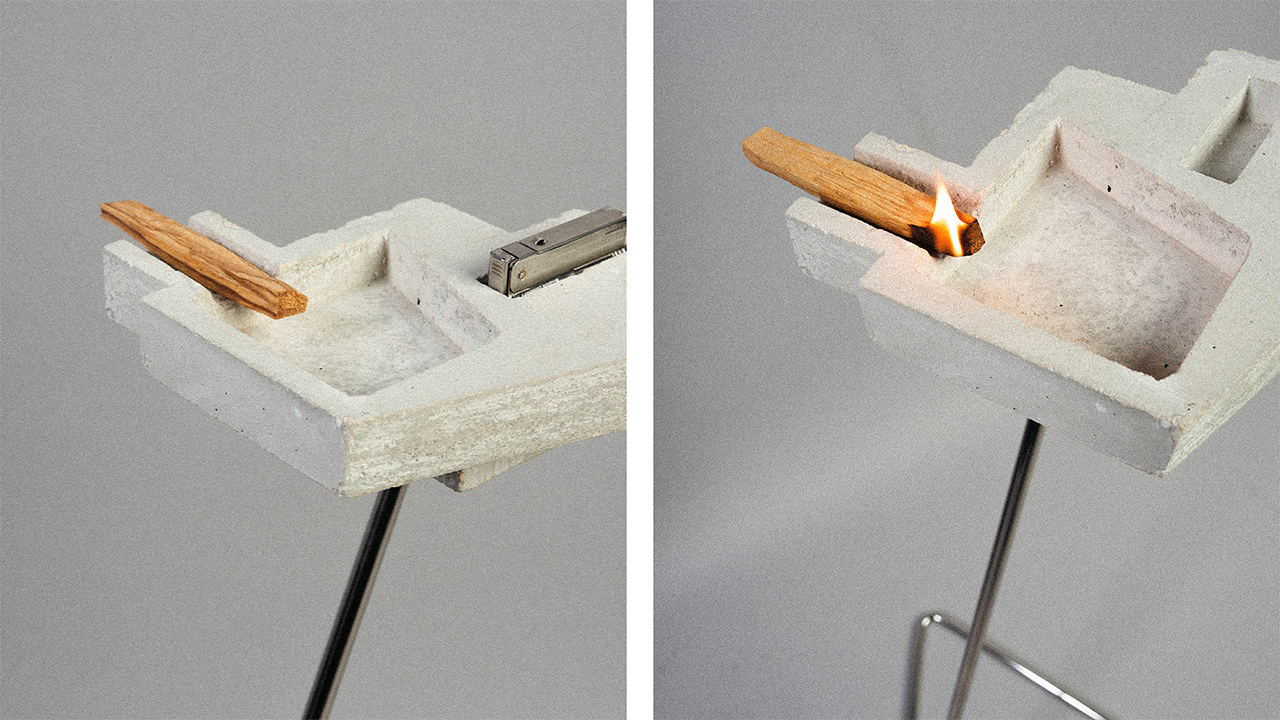

CENICERO

Max Stroh

This project addresses a common problem in modern working life. Short breaks at home or in the office often do not feel restful and usually end with people reaching for their mobile phones. The aim is to find a better alternative that effectively reduces stress.

The central idea is to use Palo Santo wood during breaks. Also known as ›holy wood‹, Palo Santo has been used for thousands of years by indigenous South American peoples, such as the Incas, in spiritual and healing rituals. The aromatic smoke produced by burning or heating the wood is traditionally used for cleansing rooms energetically and dispelling negative energies.

The central idea is to use Palo Santo wood during breaks. Also known as ›holy wood‹, Palo Santo has been used for thousands of years by indigenous South American peoples, such as the Incas, in spiritual and healing rituals. The aromatic smoke produced by burning or heating the wood is traditionally used for cleansing rooms energetically and dispelling negative energies.

The wood's calming effect is attributed to its high limonene content, which has been proven to relieve stress and anxiety. The goal is to create a simple yet effective activity for breaks. It helps clear your head and improves concentration afterwards, providing a simple alternative to scrolling on your mobile phone.

↘

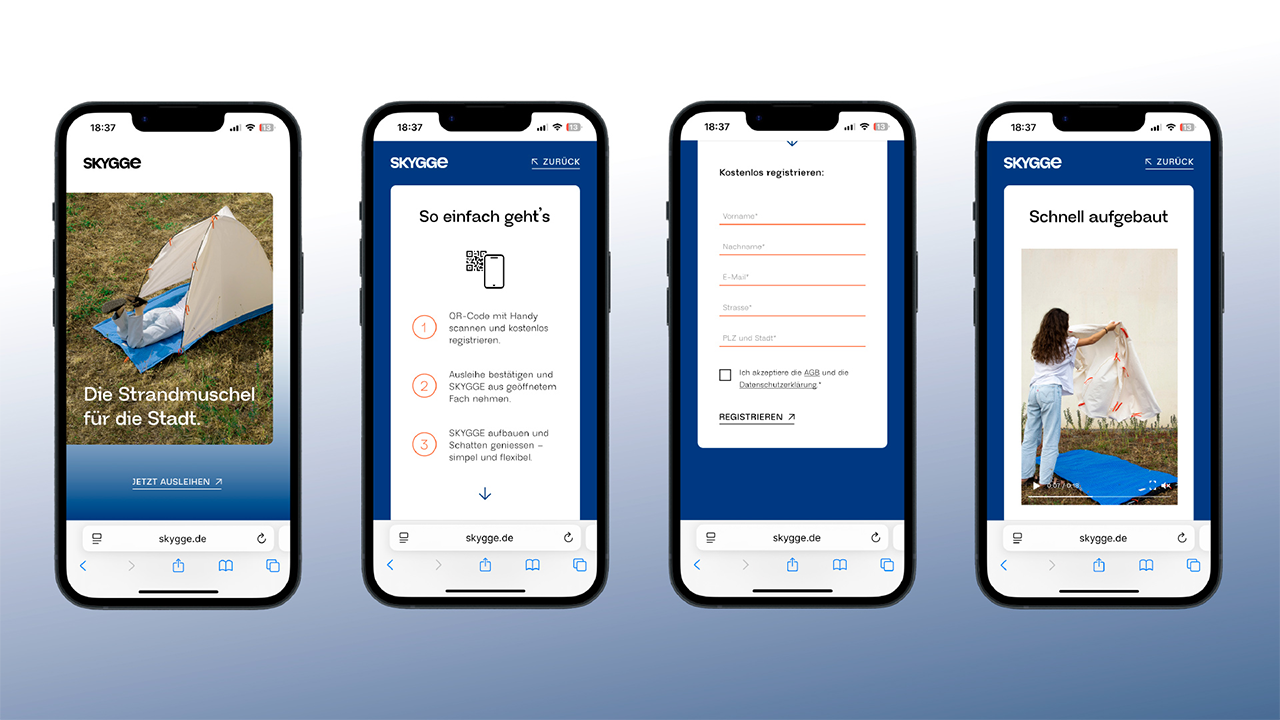

SKYGGE

Nicole Jansen, Josefine Holmer

Skygge was born out of a desire to provide people with a relaxing break from their everyday lives. Through conversations with various individuals, we identified the need for time out in green spaces. This inspired our goal of designing a tool that would enable people to take spontaneous, flexible breaks in the shade right in the city. We wanted to create a product that would be accessible to all, regardless of financial circumstances. This resulted in the concept of access points, where Skygge is made available to residents and visitors free of charge. Financed by local authorities and organisations, the city becomes more liveable for everyone.

Using Skygge is quick and easy: simply scan the QR code at the access point to access the website and register for the rental system. Thanks to the electricity generated by solar panels, Skygge can also be used to charge electronic devices on the go.

The web application visually conveys the Skygge experience with clear typography, easy-to-understand user guidance, and a consistent colour scheme. The brand thus conveys a feeling of summery lightness and simple handling.

The web application visually conveys the Skygge experience with clear typography, easy-to-understand user guidance, and a consistent colour scheme. The brand thus conveys a feeling of summery lightness and simple handling.

↘

Flare

Julia Dawn Tirol de Sousa

Flare is a kinetic mobile that acts as a mindful timer for people with ADHD. It divides the day into 45-minute work sessions, each followed by a 10-minute break. At the end of each unit, a soft light comes on and the mobile starts to move. These calm movements encourage you to let your gaze wander, helping you to enter a meditative state. By focusing on Flare's gentle movements, users are encouraged to consciously disconnect from their mobile phones and external stimuli, creating a calm and grounded break between tasks.

↘

Körperl(ich)

Isabel Leganyi

The starting point for my project was the question: How can I express the signals and sensations of my body and invite others to empathise with my physical experience and consciously perceive their own?

I began with guided body meditations. As I tuned into these states, I drew intuitively and directly, without striving for perfection, but rather from the moment. The materials I used included wax crayons, paper, cardboard, and later also a hot glue gun and various textured surfaces. The original plan was to create a large canvas painting with haptic elements. But in the course of the process, I realised that the sketches, artefacts and fragments that emerged during the experimentation already had their own powerful expressiveness. Each drawing became an immediate imprint of a specific physical sensation: spontaneous, uncensored and direct.

I began with guided body meditations. As I tuned into these states, I drew intuitively and directly, without striving for perfection, but rather from the moment. The materials I used included wax crayons, paper, cardboard, and later also a hot glue gun and various textured surfaces. The original plan was to create a large canvas painting with haptic elements. But in the course of the process, I realised that the sketches, artefacts and fragments that emerged during the experimentation already had their own powerful expressiveness. Each drawing became an immediate imprint of a specific physical sensation: spontaneous, uncensored and direct.

Instead of working towards a final piece, I consciously decided to collect these intuitive artefacts. The 30 finished drawings represent different states of my body, tension, lightness, pressure, flow – captured in the moment. In this project, I not only learned to feel my body more consciously, but also to actively use breaks by drawing in precisely these moments.

Körperl(ich) invites us to refocus on feeling – away from constant thinking, towards the body.

Körperl(ich) invites us to refocus on feeling – away from constant thinking, towards the body.

↘

Entfernte Nähe

Sebastian Meier

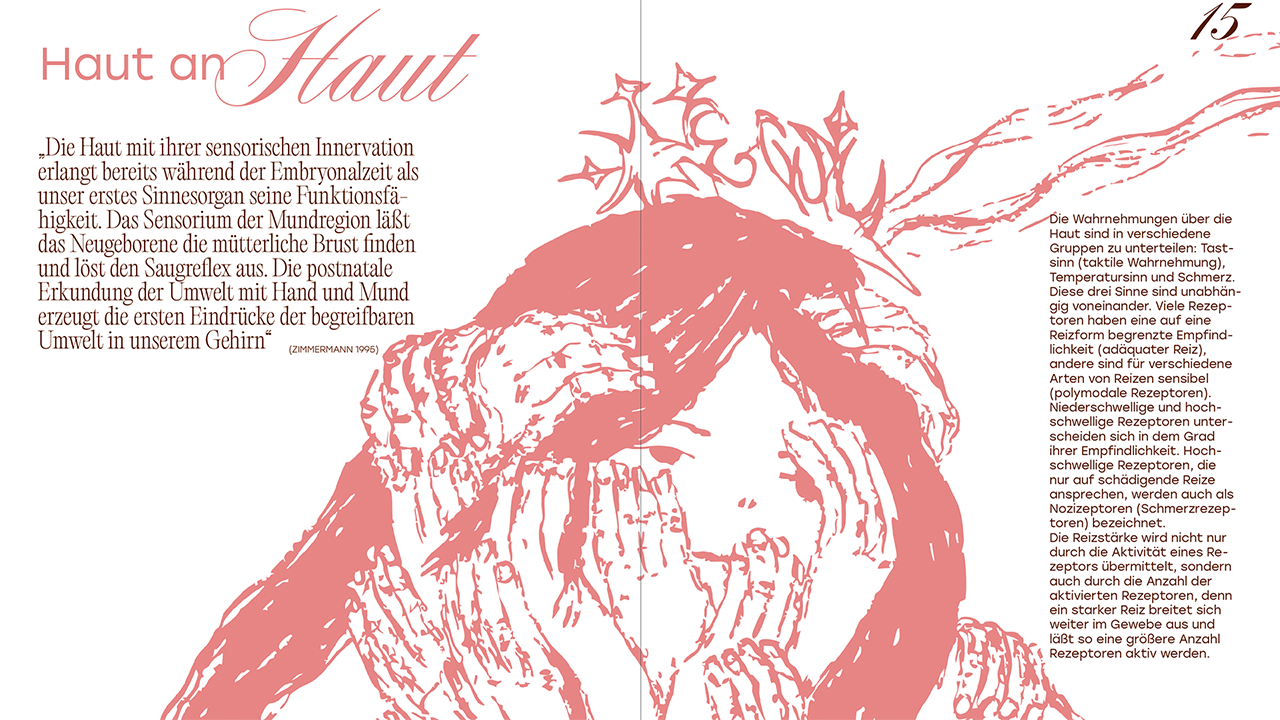

Closeness, touch and affection are basic human needs. Yet in today's society, these needs are often met with prejudice, sexualisation and romanticisation. Touch is often only accepted and experienced in romantic sexual relationships, despite the fact that it could be so much more. During the development of a cuddle-object, I created various prototypes and experimented with different materials, sizes and fillings. Magnets sewn into the fingertips and the tops of the hands enable the cuddly toy's hands to interlock and hold each other. The teddy fleece provides structure and depth to the piece, and feels comfortable without being overly synthetic. Abstract patterns are incorporated into the connecting piece between the hands, tying in with the magazine's illustration style.

The magazine explores topics such as the biological and psychological effects of touch, and provides an overview of interpersonal touch. It also questions learned rules, values, boundaries and spaces to raise awareness of ourselves and others. Uta Wagener's book Fühlen – Tasten – Begreifen (Feeling – Touching – Understanding) was central to this, providing the basis for the magazine's content accompanying the cuddle-object. As the topic also touches on very personal and intimate levels, I decided to explore it through my own lyrical texts, creating an emotional depth.

↘

kopfhoch

Emelie Glass

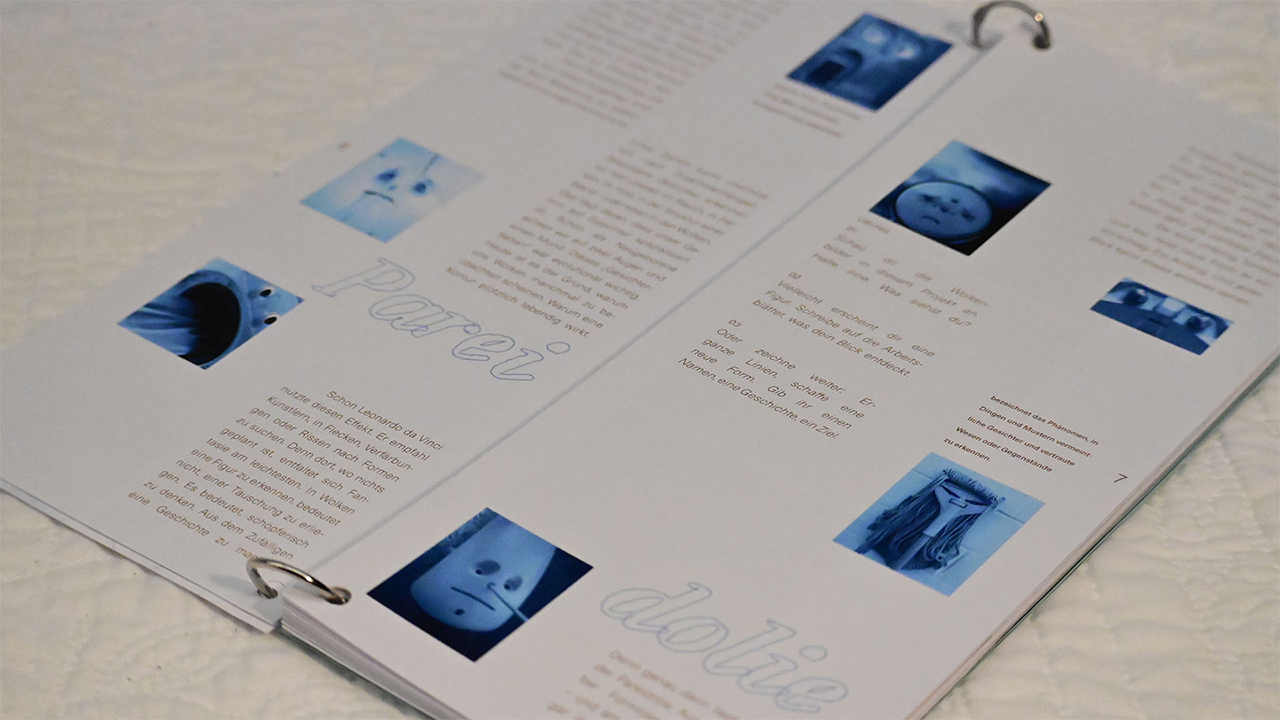

This project explores the connection between observation, language, and imagination. Kopfhoch (Head Up) is a workshop box that encourages participants to find stories in the clouds and experience the playful, open-ended nature of writing. The starting point is the question: What happens when you see the sky not just as a weather phenomenon, but as a reflection of your inner life, memories, and imagination?

The box is intended for writers, learners and storytellers, and can be used in German lessons as a creative introduction to literary writing, or in therapy as a reflective tool. It contains a magazine with five chapters (including ones on sky gods, clouds on other planets, and idioms related to the sky); cards with narrative prompts; visual cloud shapes that can be used to build narratives (based on methods such as narrative exposure therapy); and cloud Polaroids to inspire you.

The box is intended for writers, learners and storytellers, and can be used in German lessons as a creative introduction to literary writing, or in therapy as a reflective tool. It contains a magazine with five chapters (including ones on sky gods, clouds on other planets, and idioms related to the sky); cards with narrative prompts; visual cloud shapes that can be used to build narratives (based on methods such as narrative exposure therapy); and cloud Polaroids to inspire you.

The box's design is clear and almost ethereal, and its approach is open: it does not seek to guide, but to accompany and make storytelling accessible. Thus, observing the sky becomes an invitation to tell stories, to remember and to transform.

↘

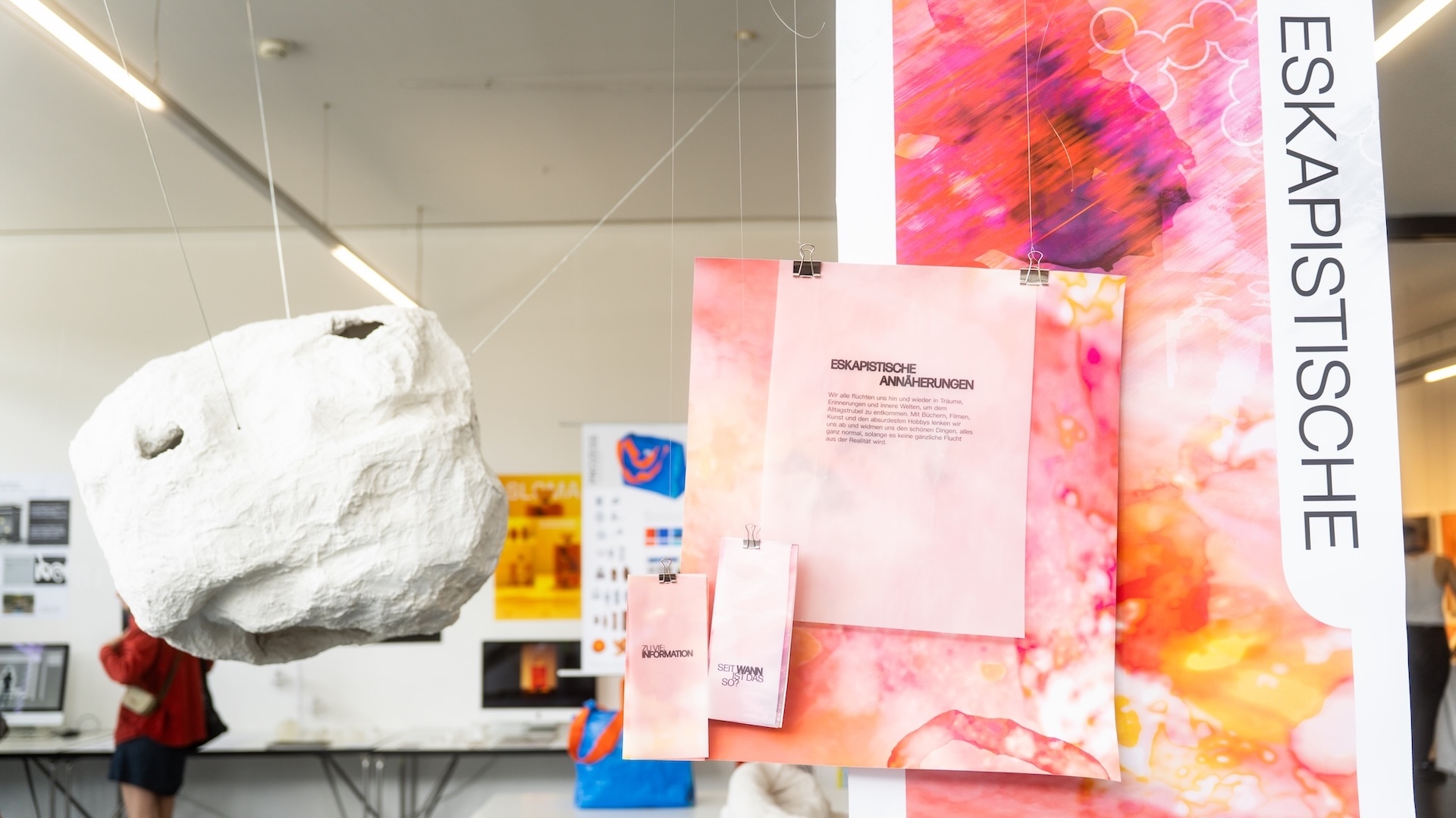

Eskapismus

Jule Derra

Zwischen Traumwelt und Realität

Escapism is the act of fleeing from reality, often by immersing oneself in books, films or stories. For a moment, we immerse ourselves in another world and leave everyday life behind. This is completely normal, and even healthy. Escapism can provide a retreat, inspiration and a creative space. However, in an increasingly digital world with constant sensory overload, we are drawn ever deeper into a maelstrom of other realities. Social media plays a dual role here: on the one hand, it overwhelms us with an endless stream of information; on the other hand, it offers us a refuge where we can immerse ourselves in the most bizarre online communities.

Escapism is the act of fleeing from reality, often by immersing oneself in books, films or stories. For a moment, we immerse ourselves in another world and leave everyday life behind. This is completely normal, and even healthy. Escapism can provide a retreat, inspiration and a creative space. However, in an increasingly digital world with constant sensory overload, we are drawn ever deeper into a maelstrom of other realities. Social media plays a dual role here: on the one hand, it overwhelms us with an endless stream of information; on the other hand, it offers us a refuge where we can immerse ourselves in the most bizarre online communities.

Escapism has many beautiful, almost magical aspects. It nourishes artistic creation and opens doors to other worlds of thought and dreams. However, it is a delicate balance. How much escapism constitutes self-care, and at what point does it become an avoidance of responsibility? How much withdrawal is necessary, and how much is comfortable, or even selfish?

I want to celebrate the optimistic, perhaps even naive, side of escapism, but also encourage reflection. We should reflect on our digital behaviour, our longings, and what it means today to really immerse ourselves.

I want to celebrate the optimistic, perhaps even naive, side of escapism, but also encourage reflection. We should reflect on our digital behaviour, our longings, and what it means today to really immerse ourselves.

↘

LUNALAY

Katharina Gorbach

›Switch the mood – keep the mode!‹

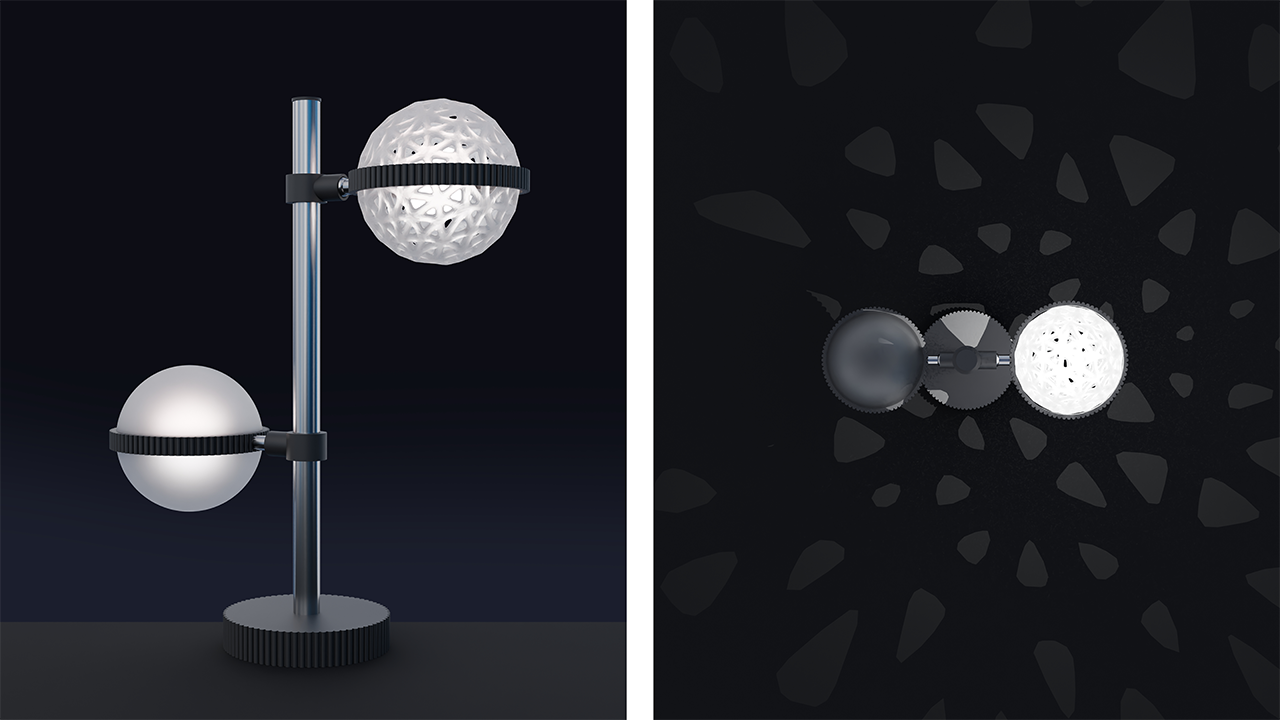

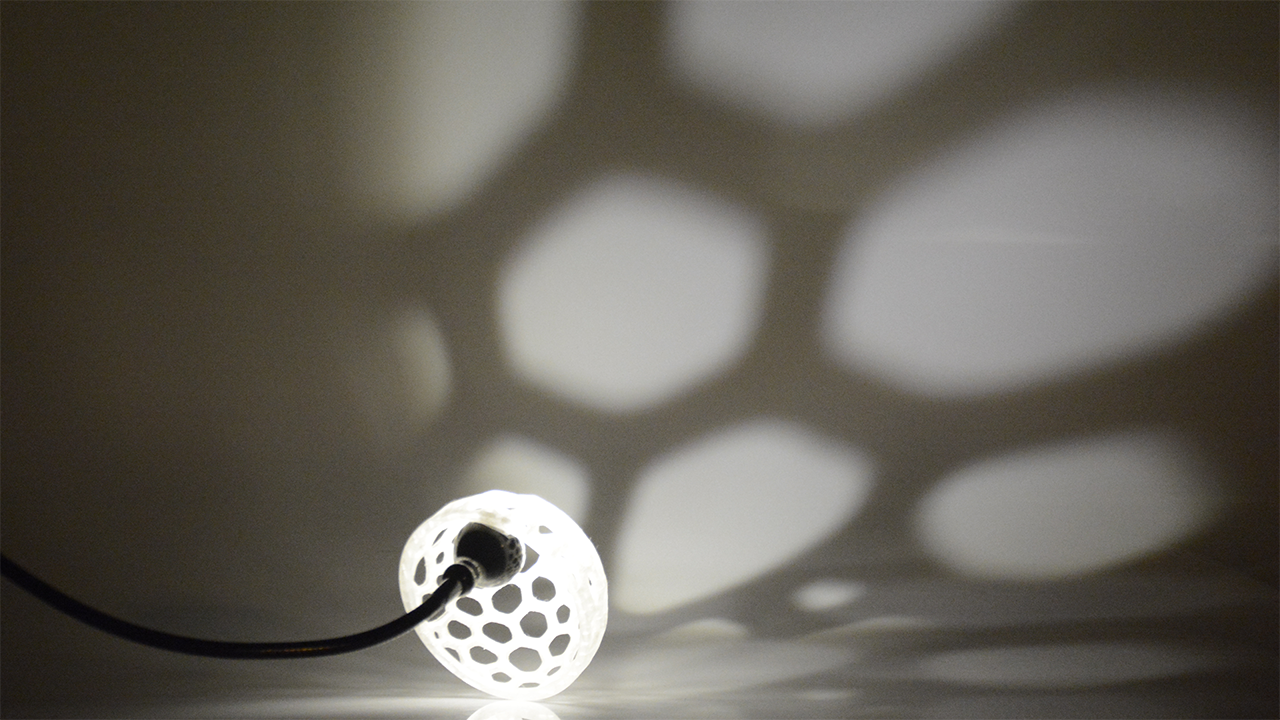

LUNALAY is an interactive lamp with three intuitive light modes to support the transition from day to night: Relaxing Mode, Reading Mode, and Sleeping Mode. The lighting promotes stillness, relaxation and calm, inviting you to disconnect from your everyday thoughts and ease into a restful state. Two rotatable spheres create a unique play of lights: One has a textured surface inspired by kaleidoscopes and creates warm ambient light patterns. The other has a smooth surface and provides neutral, focused reading light.

A touch sensor on the base allows you to switch between modes. The light elements are modular, height-adjustable and replaceable.

LUNALAY is an interactive lamp with three intuitive light modes to support the transition from day to night: Relaxing Mode, Reading Mode, and Sleeping Mode. The lighting promotes stillness, relaxation and calm, inviting you to disconnect from your everyday thoughts and ease into a restful state. Two rotatable spheres create a unique play of lights: One has a textured surface inspired by kaleidoscopes and creates warm ambient light patterns. The other has a smooth surface and provides neutral, focused reading light.

A touch sensor on the base allows you to switch between modes. The light elements are modular, height-adjustable and replaceable.

A ball joint enables the light to be focused as required for either direct or indirect illumination. Drawing inspiration from natural light phenomena, LUNALAY creates atmospheric effects on surrounding walls. The lenses of the spheres were 3D-printed and tested in multiple iterations to fine-tune the light effect and quality. Combining thoughtful design with calming visual effects, LUNALAY becomes a personal evening companion, providing more than just light – it is a gentle guide to sleep.

Lücke

Lücke